MONU #29 | Narrative Urbanism

A review of issue 29 of MONU (Magazine on Urbanism).

Follow link to read on the MONU website. Scroll or search for text in-page.

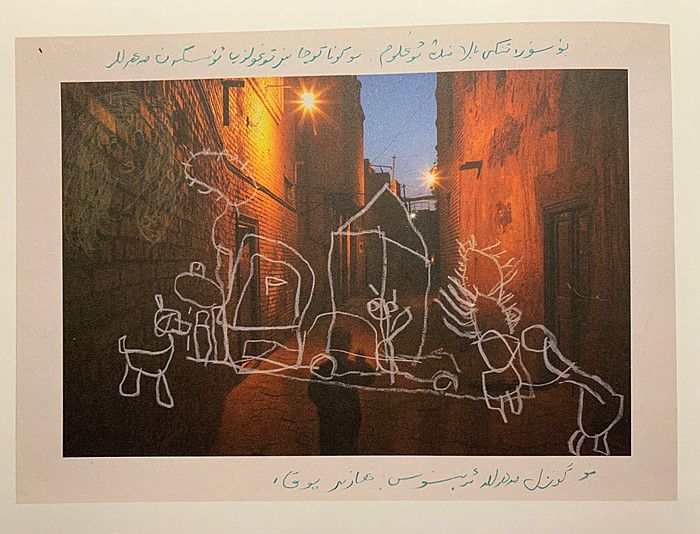

Image from Carolyn Drake’s contribution “Wild Pigeon” (p. 78)

Image from Carolyn Drake’s contribution “Wild Pigeon” (p. 78)

In MONU #29 the word “storytelling” takes on the grand connotations typically associated with architecture — futuristic visions, imposing scale, immense risk — while continuing in the tradition of gossip, morals and myths, performances and gestures. In this issue of MONU these folkloric traits are traced in urban development and design processes, physical explorations and creations; urban structures are built and sustained by layered, conflicting stories and the bodies that live them, eternally (re)shaping cities and histories. This “narrative urbanism” is a patient, organic process revealing every construction site and street corner as a haunted site with stories past and passing by.

This issue’s contributors encourage, with inventive narratives of their own, urban narratives that saturate sidewalks, geographies, master plans, and cities’ strategies. They also dissect the (inter)action within and between cities worldwide and promote an understanding of stories — both blueprinted and instinctive — that flow between all members of the urban ecosystem. In narrative urbanism, dormant stories are resurrected, imagined stories are drafted, and “every space is special and worthy of care,” sharing Donna Haraway’s belief in ‘being-with’ one another and our Earth (Shepard, 6).Furthermore, I appreciate that “Narrative Urbanism” and its writers aren’t reluctant to discuss the fact that formal plans are normally exclusive, taking a conciliatory approach to the stakeholders at large. This is especially effective following MONU #28 — an issue dedicated to the ins and outs of “Client-Shaped Urbanism”.

Early on in the issue, Omar Kassab’s “Narrative is the New Black” comes as a surprise, happily upsetting our notions of narrative. Opening with a matter-of-fact summary of the rapid decline of modern languages spoken and written today, the piece prepares us for “an approaching all-out metamorphosis” of language and narration that seems obviously bleak (Kassab, 13). He reviews the ways in which language has been constrained, namely by our general focus on the written word, marking its limitations and how thoughts and feelings can be cut short on the page or when spoken. The conventional methods of expressing ourselves taught to us by parents, textbooks, and teachers have never been all-embracing; rather they’ve dampened our individual, inner-to-outer communications.

At the same time Kassab outlines the rise of visual culture, the growing prevalence of visual tools of communication, and the global expansion of the virtual field. Visuo-virtual narratives, he argues, are more colloquial, easily disseminated, and can express what spoken and written languages cannot on their own; they promote well-rounded, globalized communication, contributing to an evolution in storytelling. Though I felt that familiar, faux indifference when he mentioned emojis and internet memes, by the end of “Narrative is the New Black” I had to appreciate the engaging possibilities to be found in narrating language itself. These visual mediums can be flighty and whimsical, but it is undeniable that using such visually rooted languages alongside text and sound encourages large-scale collaboration, “a wondrously complex amalgamation of a language” (Kassab, 14).

Kassab points out a simple, persistent fact that underlies each piece in MONU #29: like words, urban narratives are generative, utilized best if all stories — architects’, artists’, friends’, neighbours’ — are included to construct our futures in cityscapes.On the other hand, urban narratives are unlike words in the sense that they grapple directly with physical space, bringing cities and citizens together, and touch all of our senses. This reminded me of Ingold’s concept of “languaging” found in artist Emma Smith’s Practice of Place, a similarly celebratory text I would consider MONU #29’s companion piece:

Far from serving as a common currency for the exchange of otherwise private, mental representations, language celebrates an embodied knowledge of the world that is already shared thanks to people’s mutual involvement in the task of habitation. It is not, then, language per se that ensures the continuity of tradition. Rather it is the tradition of living in the land that ensures the continuity of language. (Smith, 153; Ingold, 147)

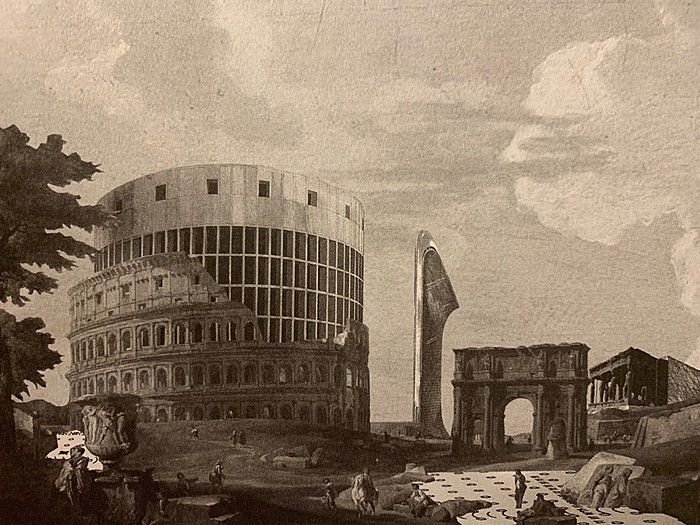

Image from WAI Architecture Think Tank (Garcia and Frankowski)’s article “The Rise of the Kynics” (p. 91)

Image from WAI Architecture Think Tank (Garcia and Frankowski)’s article “The Rise of the Kynics” (p. 91)

“Narrative Urbanism” also examines a collection of visual and physical narrative methods that alternate between subverting and complementing those established when only professionals and moneyed influencers hold sway over a building, district or project. Many of the articles take on a propositional tone, determined to add oral histories, collective memories, and archival materials to the canon of professional narratives that include architectural renderings, staid agreements, and buzzword-y PowerPoints. This method of legitimizing urban storytelling — by way of expanding, compiling, and mobilizing an array of urban voices — is meticulous yet passionate.

My favourite pieces demonstrate narrative urbanism as an everyday practice — one that is clamorous and made up of countless, assorted bodies moving and speaking at once. They also celebrate my favourite urban movement: walking. “Talk on the Wild Side: Moving Beyond Storytelling in Cities” and “Right to the Narrative — Walking Interviews” describe action-based methods of collective walking and urban exploration that encourage communities and residents to “co-author” underused and undeveloped urban spaces. The authors of the respective articles offer fieldnotes and quotations that are honest reflections from their participants. In an attempt to“both inspire and provoke people to question the received narrative of their city and embark on new ones that they can own and develop collectively,” they take community members and urbanists on ‘nightwalks’ and invite them to go ‘wastelanding’ i.e. observe abandoned or neglected spaces (37).

This urban choreography, along with the accompanying images of deserted, concrete areas in the article, reminded me of years spent purposefully loitering when I was a teenager. I shuttled between New York and New Jersey, searching for ways to hide in plain sight; sometimes my friends and I sought out blind spots, or unclaimed land, in parking garages and suburban forests. I imagine what I would say to those moving with me if I were to go on a collective walk through those dead spaces again. I wonder what affect this method would have on my, and everyone else’s, everyday actions. Would my friends and I have continued killing time in convenience stores, flipping through magazines, trying to look like we’d just arrived or were just about to leave? Would we still hide from the cops in public parks after dark, determined to conduct our late-night sports and teen rituals in peace? Maybe we would have inhabited more (or less) conspicuous spaces, or maybe our cities’ parent-teacher associations, city council members, business owners and the police officers would simply have a better understanding of what we wanted, which was simple: ownership of public spaces, fewer spatial regulations, and the right to lazily traverse cities, to ride to and from Manhattan with ease and clear conscious. Though we definitely enjoyed carving out our own spaces, making them simultaneously Other and ourselves. And I still wish for the same; as a woman who loves cities’ nightlife in particular, I want to claim my movements and co-design urban spaces entirely. That being said, it is clear, from my own experiences and the ones displayed in these articles, that these desires aren’t reserved for youth culture; I and many others haven’t abandoned our need to explore, dominate, and affect parts of our cities we crave or already crawl all over and adore.

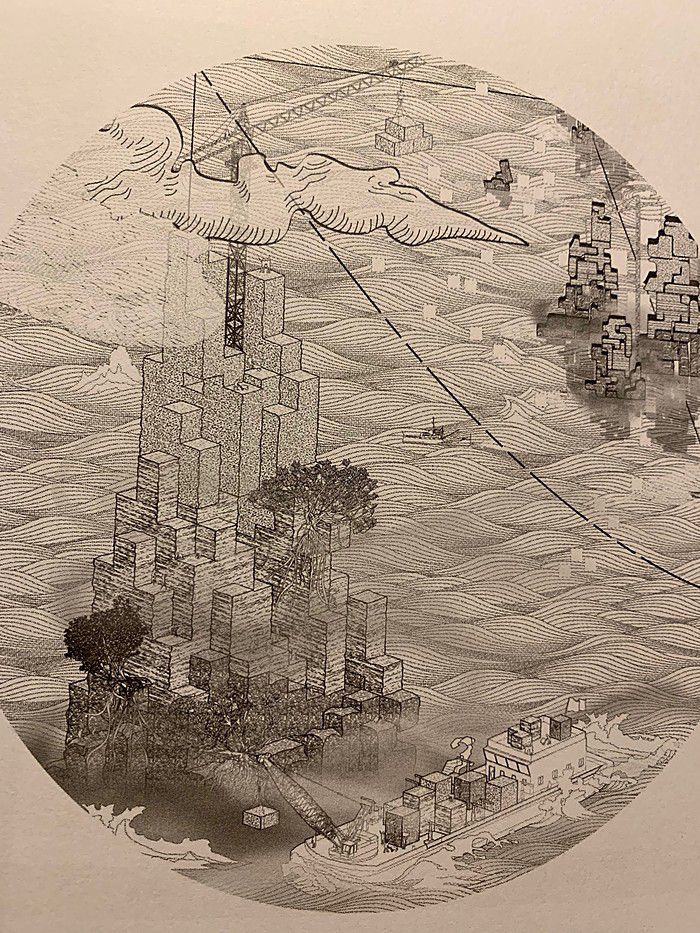

Image from MAP Office (Gutierrez and Portefaix)’s piece “Hong Kong Is Land” (p. 21)

Image from MAP Office (Gutierrez and Portefaix)’s piece “Hong Kong Is Land” (p. 21)

“Narrative Urbanism” also reminds us that stories are not only told by bodies but are embedded in cities’ foundations, continuously shaping urban forms each day. “The Grid and the Bedrock”, for example, displays and explains literal (re)drawings of history via four consecutive maps of Manhattan affected by ecological changes, advanced infrastructure, and wars. “Geostories” and “The Rise of Kynics” feature eerie, seemingly unnatural collages and diagrams influenced by the same urban changes,though these images are completely sensible when viewed through the lens of architectural history and the Anthropocene. Meanwhile, “Hong Kong is Land” is a striking future narrative of Hong Kong; the artists and architects of MAP Office have drawn mythological maps of eight new islands to add to its surrounding landscape. Responding to universal urban issues and wide-ranging narratives, the proposed islands are delicately drawn fantasies with names such as “The Island of Self,” “The Island of Resources,” and “The Island of Possible Escape.”

American photographer Carolyn Drake also reflects on the temporal and imaginary aspects of narrative through her co-created photographic images. Maybe the most visceral pieces in “Narrative Urbanism”, they are manifestations of the tumultuous relationship between Uyghur people, based in a remote province 2,000 miles from Beijing, and manipulations of their space and culture. Both the government’s development policies (which are aggressively modernizing their villages and cities) and Drake’s photographic actions challenge the narratives they want to persist and the truths they wish to speak in the face of oppressive authorities. The photographs presented were supplied by Drake and collaged and sketched on by Uyghur citizens. The images reveal tangible ‘lines of desire’ in the community, cut out, adhered, and rearranged according to unique perspectives from the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region. I think they signify strong environment ‘reflextion’ — a reflex to and reflection on the environment and cultural and political situation. These cut-and-paste photographs also seem to parallel the dense, carnival-coloured illustrations in “Bangkok Domestic Tastes”; just as the collaborative artworks seem to make Uyghur inclinations and emotions clear, the collage-like images of Bangkok neighbourhoods curate the real estate market’s strategies as abstract spaces and shapes that align aspirational modes of urban living.

“Narrative Urbanism” succeeds in “describing without dictating” in a way that proves it to be an inclusive, communicative, and forthright addition to urbanism methodologies (Ng, 110). As a method that is at once unique and diverse, ever-changing and steadfast, it is indeed narrative urbanism that excites city living, activates urban design, and gives architecture its grand connotations.